The concept of patriotic hacker can be understood as the attacker, in the cyber field, whose activities support in one way or another his country in a real conflict, directed against the enemy of the state ([1]). Along with China, Russia has been perhaps one of the countries that has most empowered these groups, active for years in conflicts such as Kosovo (1999), Estonia (2007) or Georgia (2008). In Spain, if there has ever been something similar and in any case not state sponsored, it could be linked to small actions in the network against the environment of ETA after the murder of Miguel Angel Blanco (1997), perhaps at odds between hacktivism and patriotic hackers (this would give for an interesting debate), but in any case very far from the activities of patriotic groups in other conflicts or countries.

The concept of patriotic hacker can be understood as the attacker, in the cyber field, whose activities support in one way or another his country in a real conflict, directed against the enemy of the state ([1]). Along with China, Russia has been perhaps one of the countries that has most empowered these groups, active for years in conflicts such as Kosovo (1999), Estonia (2007) or Georgia (2008). In Spain, if there has ever been something similar and in any case not state sponsored, it could be linked to small actions in the network against the environment of ETA after the murder of Miguel Angel Blanco (1997), perhaps at odds between hacktivism and patriotic hackers (this would give for an interesting debate), but in any case very far from the activities of patriotic groups in other conflicts or countries.

In Russia, different groups have been identified that could be called Kremlin-related groups (from Chaos Hackers Crew in 1999 to Cyber Berkut, active in the conflict with Ukraine) and their actions, groups that have focused their activities on defacements and, in particular, in DDoS attacks against targets that have been considered contrary to Russian interests. From each of the operations of these groups there is literature and more literature. An excellent summary of the most notorious can be found in [8]. As early as 1994, in the First Chechen War, some patriotic groups used the incipient web for PSYOP, at that time with Chechen victory, a victory that would change sides later (1999) in the Second Chechen War ([3]). Years later, in 2007, Russia launches a cyber-attack against Estonia that stops the operation of the online banking of the main Estonian banks, blocks access to the media and interrupts communications of the emergency services ([4]); but there are no deaths or injuries on either side, unlike what happens a little later (2008) in Georgia, where there is a hybrid attack- the first known case in history – consisting of cyber-attacks and an armed invasion. A conflict in which different groups arise that encourage attack – in particular, through DDoS on the websites that support the opposite side. These denial attacks differed from those launched against Estonia: not only were they injecting large volumes of traffic or requests against the target, but also using more sophisticated techniques, such as using certain SQL statements to introduce additional load into this objective, thus amplifying the impact caused.

At about the same time as Georgia’s, Lithuania gets its turn, also in 2008 and, as in Estonia, in response to political decisions that their Russian neighbors do not like. In this case the Lithuanian government decides to remove the communist symbols associated with the former USSR, which causes denial of service attacks and defacements of web pages to locate in them the hammer and the sickle. A few months after the actions in Lithuania, attacks on Kyrgyzstan begin, already in 2009 and again after political decisions that the Russians do not like, now regarding the use of an air base of the country by the Americans, key for the American deployment in Afghanistan. In this case it is about DDoS attacks against major ISPs in the country, which further degraded the already precarious Kyrgyz infrastructures, originated in Russian addresses but, according to some experts, with much more doubt in the attribution than other attacks of the same type suffered previously by other countries. Also in 2009 Kazakhstan, another former Soviet Republic – and therefore of prime interest for Russian intelligence – suffers DDoS attacks following statements by its President criticizing Russia.

Finally, as early as 2014, The Ukraine becomes another example of a hybrid war, as it happened in Georgia years ago, and an excellent example of the Russian concept of information warfare, with attacks not only by DDos, but especially by disinformation through social networks: VKontakte, supposedly under the control of Russian services (we spoke before about their relationship with companies, technological or not). It is the most used social network in Ukraine, which offers an unbeatable opportunity to put in practice this disinformation ([6]). For different reasons, including the duration of the conflict itself, The Ukraine is an excellent example of the role of patriotic hackers on both sides (Cyber Berkut on the Russian side and RUH8 on the Ukrainian side), supporting traditional military interventions, putting into practice Information warfare, psychological operations, DDoS, attacks on critical infrastructures …

The presence and operations of Russian patriotic hackers seems indisputable. The question is to know what relationship these groups have and their actions with the Kremlin and its services, if any, and the degree of control the Russian government may have over them … and even its relationship with other actors of interest to Russian intelligence, such as organized crime, which we will discuss in the next post of the series. Actions such as those executed against Ukrainian servers in 2014 by Cyber Berkut showed TTPs very similar to those previously used in Estonia or Georgia, which would link these actions not only to properly organized groups, but would also lead to a possible link with The Kremlin, following the hypothetical attribution of these last actions with the Russian government ([2]).In [9] an interesting analysis is made of the relationship between patriotic hackers, cybercrime and Russian intelligence during the armed conflict with Georgia in 2008. In addition, in the tense relations between Russia and Georgia, there is another hypothetical proof, especially peculiar at least, of the link between attacks, patriotic hackers and Russian services: in 2011, the Georgian government CERT ([7]), before a case of allegedly Russian espionage, decides to voluntarily compromise a computer with the malware used by the attackers, put a lure file on it and in turn to trojanize said file with remote control software. When the attacker exfiltrated the honeypot, the CERT was able to take control of his computer, recording videos of his activities, making captures from his webcam and analyzing his hard disk, in which emails were supposedly found between a controller – from the FSB, so the evil tongues of some analysts say, who knows … – and the attacker, exchanging information of objectives and information needs and instructions on how to use the harmful code.

Regardless of the relations of the Russian services with groups of patriotic hackers, the infiltration or the degree of control over them, what is certain is that in certain cases the FSB has publicly avoided exercising its police duties in order to pursue a priori criminal activities by Russian patriotic hackers: in 2002, Tomsk students launched a denial of service attack against the Kavkaz-Tsentr portal, which housed information on Chechnya annoying for the Russians. The local FSB office issued a press release in which it referred to these actions of the attackers as a legitimate “expression of their position as citizens, worthy of respect” ([5]). And what is indisputable is that after decisions made by a sovereign government that may be contrary to the interests of the Russian government or simply to their opinion, that government suffers more or less severe attacks – depending on the importance of that decision – against its technological infrastructures, at least in areas especially relevant to Russian intelligence and government such as the former Soviet Republics. Of course, attacks that are difficult to reliably link to the Russian government or patriotic hackers of this country, but they occur in any case.

Finally, one more detail: Russian patriotic hackers have not only executed actions against third countries, but also operated within the RUNet. One of the most well-known cases is that of Hell, acting against Russian liberal movements: opponents of the government, journalists, bloggers … and of which there have been signs of their connection with the FSB (let’s remember, internal intelligence) specifically with the CIS of this service. In 2015 Sergei Maksimov, allegedly Hell, is tried and convicted in Germany for falsification, harassment and information theft. Although facing three years in prison, the sentence imposed is minimal. Was Maksimov really Hell? Were there any links between this identity and the FSB? Was Hell part of the FSB itself, unit 64829 of this service? Nor do we know, nor will probably ever know, as perhaps we do not know whether Nashi, a patriotic youth organization born under the protection of the Kremlin – this we do know, as it is public – organized DDoS attacks not only against Estonia in 2007, but also against Russian journalists opposed to Putin’s policies, and also tried to turn to journalists and bloggers for their support in anti-deposit activities in the Russian government … at least that is what the emails stolen by Anonymous- allegedly, as always, from Kristina Potupchik, spokesperson for Nashi at the time and later “promoted” to Internet project manager of the Kremlin, say (this is also public).

References

[1] Johan Sigholm. Non-State Actors in Cyberspace Operations. In Cyber Warfare (Ed. Jouko Vankka). National Defence University, Department of Military Technology. Series 1. Number 34. Helsinki, Finland, 2013.

[2] ThreatConnect. Belling the BEAR. Octubre, 2016. https://www.threatconnect.com/blog/russia-hacks-bellingcat-mh17-investigation/

[3] Kenneth Geers. Cyberspace and the changing nature of warfare. SC Magazine. July, 2008.

[4] David E. McNabb. Vladimir Putin and Russian Imperial Revival. CRC Press, 2015.

[5] Athina Karatzogianni (ed.). Violence and War in Culture and the Media: Five Disciplinary Lenses. Routledge, 2013.

[6] Andrew Foxall. Putin’s Cyberwar: Russia’s Statecraft in the Fifth Domain. Russia Studies Centre Policy Paper, no. 9. May, 2016.

[7] CERT-Georgia. Cyber Espionage against Georgian Government. CERT-Georgia. 2011.

[8] William C. Ashmore. Impact of Alleged Russian Cyber Attacks. In Baltic Security and Defence Review. Volume 11. 2009.

[9] Jeffrey Carr. Project Grey Goose Phase II Report: The evolving state of cyber warfare. Greylogic, 2009.

Image courtesy of Zavtra.RU

We cannot conceive the Russian intelligence community, described in this series, as a set of services dependent on political or military power. The degree of penetration of these services throughout Russian society is very high, both officially and unofficially. It is no secret that former KGB or FSB officials occupy positions of responsibility in politics or big companies in the country. As a curiosity, in 2006 it was reported that 78% of the country’s top 1,000 politicians had worked for the Russian secret services [1]. So much so that these profiles have a proper name: siloviki, a term that comes to mean people in power. And it is no secret who is the most well-known siloviki: Vladimir Putin, President of the Russian Federation, who was agent of the KGB in the Soviet era and later Director of the FSB.

We cannot conceive the Russian intelligence community, described in this series, as a set of services dependent on political or military power. The degree of penetration of these services throughout Russian society is very high, both officially and unofficially. It is no secret that former KGB or FSB officials occupy positions of responsibility in politics or big companies in the country. As a curiosity, in 2006 it was reported that 78% of the country’s top 1,000 politicians had worked for the Russian secret services [1]. So much so that these profiles have a proper name: siloviki, a term that comes to mean people in power. And it is no secret who is the most well-known siloviki: Vladimir Putin, President of the Russian Federation, who was agent of the KGB in the Soviet era and later Director of the FSB.

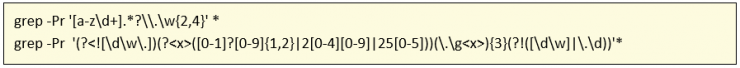

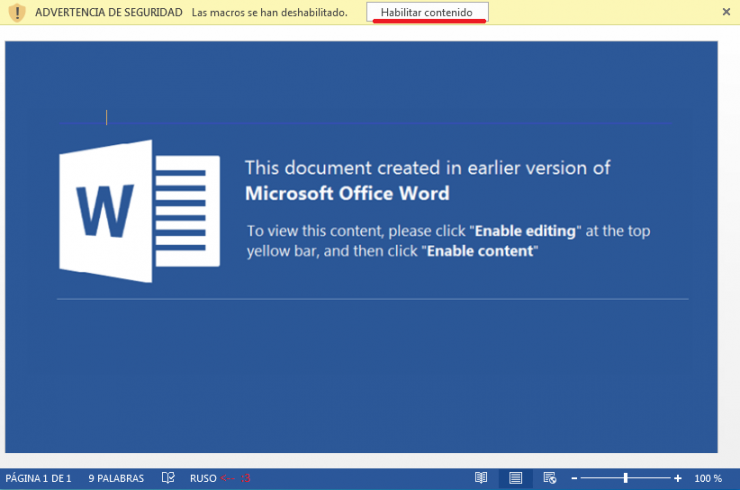

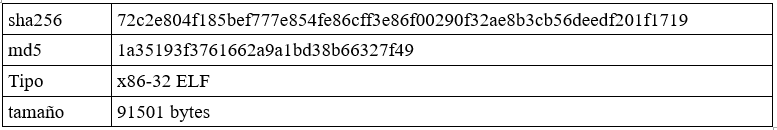

A few days ago while analyzing several emails I came across one that contained a suspicious attachment. It was a .docx document that at first glance had nothing inside but it occupied 10 kb.

A few days ago while analyzing several emails I came across one that contained a suspicious attachment. It was a .docx document that at first glance had nothing inside but it occupied 10 kb.